In an earlier post, we looked at public/private keys, cryptocurrency "wallets", signing transactions, and the user-level mechanics. To recap:

The journey of a piece of transaction data begins with its construction in the users' wallet (software or hardware). You enter in how much you want to send and to whom, and sign this message with your private key. The wallet then broadcasts this signed message to the network, and your transaction is on its way to be written onto the blockchain...

What happens next is at the node-network-miner level. Because the blockchain is decentralized and transaction data is distributed between nodes, there must be a way for the nodes to sync and agree on what transactions have already occurred. In other words, they have to be in consensus about what the blockchain looks like - a common history, if you will.

For this discussion, we explore consensus algorithms, a way to ensure that there is only "one version of the truth". It would be useless if a portion of the network held a ledger that indicated Bob has 10 BTC to spend, while the other said that he had 1 BTC to spend. To preserve the value of the coin and prevent people from spending money they don't have, the network must be in agreement about the one source of truth - the blockchain itself.

There are a few different consensus algorithms out there and this post is the first of what will be a multi-post series on widely-used algorithms. We begin by taking a closer look at the OG algorithm used in blockchains, the proof-of-work.

The idea of Byzantine fault tolerance pops up a lot when talking about consensus. It describes a property of the blockchain that allows the network to be in agreement about what history looks like, despite the presence of unreliable nodes.

Byzantine fault tolerance comes from solving an agreement problem that generally applies to distributed computing systems in which individual components may appear both failed and functioning to different observers. A closer look at the Byzantine Empire analogy...

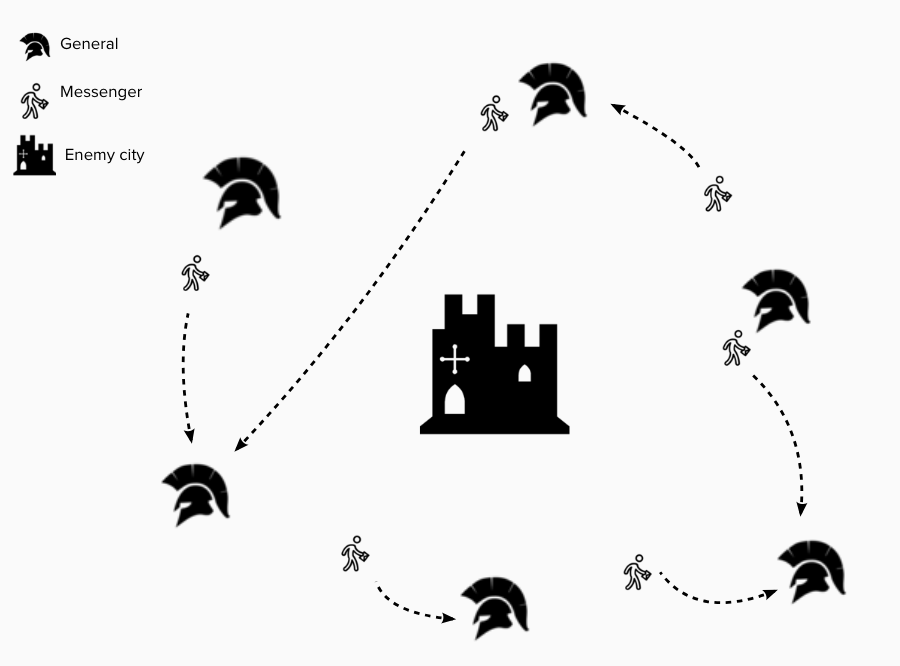

The Byzantine Empire was a civilization in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. The Byzantine Generals' Problem describes a hypothetical scenario in which a group of Byzantine generals and their respective troops surround an enemy city. To be successful in capturing the city, the generals must come to an agreement on whether to attack or retreat.

Consensus isn't achieved easily because:

Generals can only communicate via messenger, not directly to each other

One or more of the generals can be a traitor, saying he will attack and then staying put or vice versa

Some of the messengers themselves can be traitors, tasked to relay one message and delivering the opposite information

They will be successful if and only if the majority of generals agree on the decision, and collectively attack or retreat.

The difficulty lies in maintaining the integrity of the decision made by honest parties despite the presence of traitors.

For example, a corrupt messenger sent by General A may tell General B that A plans to attack, but then tells General C that A plans to retreat. The generals must make the same decision despite the fact that some of the messengers may spread lies.

In places like nuclear power plants and airplane engines, we depend on many sensors to determine the how the overall system behaves. The system needs to be Byzantine fault tolerant against misinformation from malfunctioning components.

How this relates to the blockchain

Distributed ledgers, like the blockchain, are decentralized and by definition not controlled by any central authority. It relies on the network's tolerance to peers with ill intentions - for example, those who attempt to add false transactions to the ledger. At any given point in time, we need a coherent, shared history of every transaction that has ever occurred.

The Byzantine generals above will be fault tolerant when they have a method which allows them to reliably reach consensus despite the presence of traitors trying to tamper with their efforts. It's worth noting that the specific decision isn't important, what matters is that they agree on the same one.

Mapping this analogy to the blockchain, the network is trying reach consensus on the transaction history. Because multiple miners may broadcast different data to append to the blockchain, as a Byzatine fault tolerant system the network must agree on the version of the updated blockchain they will accept as truth. It does so using these rules:

The chain with the highest cumulative proof of work (~ longest chain) always wins

The version of the blockchain the held by the majority wins

It is computationally expensive to tamper with history as the manipulated version of the blockchain will no longer match the version held by the majority of the network, and thus will not be accepted - explained towards the end of my previous post

In a network with many players and no central control, how is consensus maintained using these rules?

...it's all about incentives

A refresher on the different parties involved in a PoW-based network:

👩🏻💻 A transacting party is anyone that sends or receives coins: Senders construct and broadcast the amount and receiving address with their wallets and sign the transaction information with their private key. Their broadcasted transactions will wait to be verified by a node

Explained in detail here

🖥 A (full) node is someone with a copy of the full blockchain (the entire transaction history). Their job is to verify the transactions broadcasted by transacting parties by checking that the sender has the appropriate funds, and that the transaction signature was created using the right private key (without knowing the private key themselves) - also explained here.

Nodes add verified transactions to the mempool to be mined

⛏ A miner adds valid transactions to a block can finds a "password" (the nonce) that would allow the new block to be appended to the blockchain

Once solved, they broadcast their block and the solution to the network

...of course, any given person can fall into one, two, or all three of these categories if they have the required resources for it.

Role of transacting parties, nodes, and miners

As a business model, miners spend money on hardware and electricity in order to mine coins in return for block rewards and transaction fees. Like trying to brute-force guess an 8-character Wifi password by going through all character combinations one by one, miners must (use their equipment to) solve for the proof-of-work solution. There is no way for anyone to easily derive what the solution is, and it takes time for powerful machines to run the hashing function many times, essentially blind-guessing a password.

Block rewards are given when a miner successfully solves this computationally hard problem and gets their block appended to the chain, the miner also receives the transaction fees attached to txns in that block. You can see the newly minted bitcoin in any given block (example), it should be at the top with no input address, and the miner's wallet address as the destination.

Newly Generated (minted) bitcoins in a transaction block. Current block reward is 12.5 BTC and will halves every 4 years.

The sender needs to pay transaction fees to the miner as compensation for adding their transaction to the blockchain. The wallet software that is connected to the network will decide on the appropriate fee to attach, depending on how many people are trying to send coins at that point in time. Because miners are economically driven, they will prioritize transactions with higher fees attached to the block they are mining. Therefore,

The higher the transaction fee you pay, the faster your transaction is likely to go through

If a miner decides to solve for and broadcast an invalid block (one with false transactions), the network would reject it and the miner would have wasted their electricity on solving for the "password" that would have allowed for the block to be appended. Thus, the system is incentivizing people to play by the rules and work on valid blocks.

the network is Byzantine fault tolerant because each party is incentivized against malicious behavior.

A comparative infographic from Patricia Estevao - I've cropped a portion of it for our use but I highly recommend her portfolio for other visuals and blockchain related infographics :)

BLOCK Confirmations

A block interval is the average time it takes for a new block to be added to the chain. By design, the network is able to solve the proof-of-work problem every ~10 minutes (block intervals vary for different coins). Block intervals allow time for new data to propagate through the network.

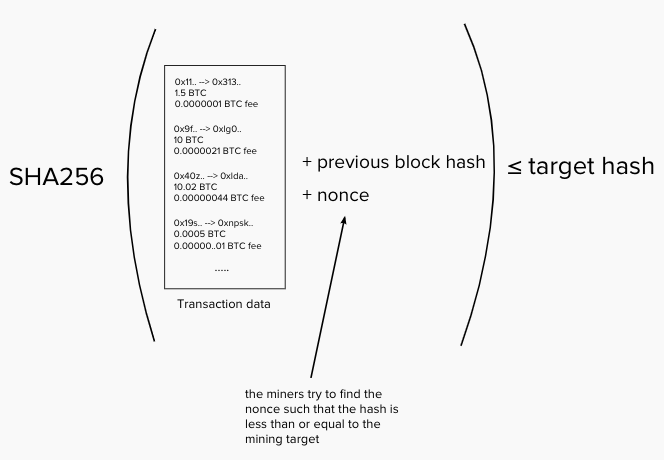

The block interval is maintained by the mining target and mining difficulty. Each miner is trying to find the nonce such that the SHA256 hash of the data, previous block, and nonce is lower than or equal to the target.

Miners use equipment to randomly guess nonces such that the SHA256 hash of the data satisfies this condition.

The mining target hash is dynamic and can be adjusted should the network solve for new blocks too quickly or too slowly. Lowering the mining target means the nonce becomes harder to find. When block intervals become to small, mining difficulty is increased and vice versa

The more miners join the field...

The higher the probability of the combined effort of the network finds a valid nonce...

The lower the mining target...

The higher the mining difficulty...

The more secure the network...

Why should we maintain block intervals?

Let's say two miners from opposite sides of the world finds the nonce (solution) at the same time, they broadcast this solution and their block, both valid, starts propagating through the network. The nodes that are geographically closest to each miner will append that miner's block to their copy of the blockchain, resulting in two "versions" of the truth.

If two miners find a solution close to each other in time, both blocks are valid, but which one the nodes receive first depend on their geographical distance from the miner. This situation can cause stale blocks

The next miner that successfully mines a block will choose which version to append to. Because the network always picks the “longest” (contains the most proof-of-work) chain, the version that this latest miner chooses will become the one accepted as truth, and the block that was appended on the other version will become a stale block -- its transactions return to the mempool waiting to be added to a new block.

...this is why you should wait for several confirmations before you can be sure that your transaction has gone through, your transaction may be accepted into a block that ends up getting "stale".

The gold rush ⛏

Mining can be a highly profitable venture. Those who were early enough in bitcoin mining will recall the days where your computer or a few graphics cards were sufficient for some mining rewards. Those days are long gone. An essential component of proof-of-work mining is the hardware, which can be generalized or specific. A quick summary of what you can use to mine coins:

CPUs (central processing units) are generalized and can perform many operations, they are what your laptops run on

GPUs (graphics processing units) are more specialized and are good with matrices operations, thus they are widely used for gaming and fast graphics renderings

ASICs (application-specific integrated circuits) are highly specialized, custom-designed for one purpose only. Bitcoin ASICs can perform SHA256 hashing very very fast. So theoretically if the bitcoin network were to switch to a different hashing algorithm other than SHA256, bitcoin ASIC farms could be rendered obsolete.

Miners calculate their chances of mining the next block by determining their hash rate (how quickly they can guess a nonce, hash the data, and check if it is lower than the mining target), and dividing this by the network hash rate (how quickly all miners in the network are doing this together).

Chances of you solving the next block = your hash rate / network hash rate

Because the network hash rate is so large, individuals usually join a mining pool for divided but more consistent returns.

A glance at bitcoin's network hash rate over time. Source: blockchain.info

After the gold rush ⚡️

As new users enter the network, we begin to see scaling issues and heated debate on how we can deal with them. Each block of the bitcoin blockchain can only hold 1MB of transaction data (this is called the block size). This means that the more transactions in the network:

The longer the confirmation time OR

The higher the transaction fees

Miners will add transactions with higher fees attached first to maximize their gains, which means you'll have to wait longer if you're paying the market-accepted fee or you'll have to attach a higher fee if you want the transaction done quickly. Let's look at some proposed solutions:

Increasing the block size

Most famously implemented by Bitcoin Cash, who increased the block size to 8MB*. Some points raised in an ongoing debate for and against this;

Technically simple because you just have to change a variable in the protocol

Not a sustainable, long-term solution because sooner or later it will also not be enough and we have to increase the block size again

May lead to centralization because now not everyone will be able to run a full node as the block sizes are too big

BCH argued that this is sufficient for now in order to allow the currency to be used for every day transactional purposes as opposed to just long term holding

Decreasing the block interval

Due to the stale block issue mentioned above, it's important to give the network sufficient time to propagate information.

We might have inconsistencies if the block intervals are too short as the network might not have synchronized properly

Layer 2 solutions - (TO BE CONTINUED)!

The solution chosen by bitcoin core team via the the Lightning network. This involves building on top of the main blockchain as opposed to addressing the problem in the core layer.

I'll dive into transaction malleability, SegWit, and the Lightning network inin a separate post

*In mid-May 2018, the protocol was upgraded via a planned hard fork to increase the block size limit to 32MB.

The discussion about the pros and cons of proof-of-work vs. other algorithms deserves several articles of its own. However, given the volume of alarmist-sounding pieces against proof-of-work mining in the media, I'd like to bring up more (rationally) optimistic points that IMO deserves more attention.

High energy consumption in mining

The sheer difficulty for miners to find the proof-of-work solution is crucial to the security of the network running on this protocol. Mining is computationally expensive by design - the electricity is being spent on securing a network that can handle global attacks by colluding nation states.

The high fixed costs of running a mining operation means that miners are economically driven to find the cheapest electricity which, at scale, will be renewable energy and not fossil fuels.

This race towards cheap electricity could therefore accelerate us towards clean energy production at scale.

10x more users doesn't mean 10x more mining. The rush to get into the mining business now is profit driven, but we are likely to see this plateau as block rewards decrease over time

In countries where renewable energy production exceeds demand, mining can turn that un-utilized energy into a store of value (bitcoin), making bitcoin an investment and subsidy in renewables as it allows projects to be amortized over a shorter period of time [14]

I highly recommend Bill Tai's article on mining and green energy production at scale, as well as Andreas Antonopoulos' remarks on bitcoin's energy consumption below:

Over the past few months it's been encouraging for me to see an increasingly diverse influx of people exploring how blockchain works and take interest in the direction the we are moving towards. This technology is something that can enable open human coordination, trust minimization, censorship resistance, fraud resistance, transparency, and decentralization at global scales. The interdisciplinary nature of the blockchain, as well as the magnitude of impact it will have (if scaled right), means no one holds all the answers and yet everyone's lives will be affected by it in some way.

It's important to look at these consensus algorithms as blueprints as opposed to strict guidelines built into every blockchain. Different projects may opt for the different algorithms that best serves their use case, and projects will have varying implementations even if they choose the same one. Knowing the core ideas and tradeoffs will help you understand and evaluate what whitepapers and blog posts are referring to and have a solid foundation from which to formulate your own opinions.

Hopefully this post has left you well-armed for the next time you hear about mining, consensus, BFT, proof-of-work, and block confirmations. Here is the roadmap I presented in my earlier post, with what we've covered here in bold.

Wallet constructs transaction, decides transaction fee (free market)

Decides inputs and outputs (input - output = txn fee)

Signs transaction using private key

Broadcasts transaction, which gets propagated to the network

Mempool

Nodes put transaction in their mempool

Wait for a miner to include the transaction in their next block

Mining

Miner includes transaction in next block

Competes with other miners to solve PoW

If win, append block to blockchain

Receive block reward + transaction fee

Wait for confirmations

Wait for several confirmations to decrease the probability of the transaction being reversed (due to being in a stale block)

Thanks for reading! Next we'll explore proof of stake. Until then, cheers.

If you appreciated the post and/or the Neil Young reference:

BTC: 3JaB3nHHfvWZVsnfHSNRepc8xAKubLSkZR 🙏🏼

Further Reading & Resources

[Wikipedia] Byzantine Empire

[Research Paper] Byzantine Fault Tolerance

[Georgios Konstantopoulos] Understanding Blockchain Fundamentals - Byzantine Fault Tolerance

Satoshi's email explaining how the proof-of-work chain leads to BFT

[CoinCentral] Mining hardware overview

[Zane Witherspoon] A Hitchhiker's Guide to Consensus Algorithms

[TechTarget] What is a Consensus Algorithm

[Blockchain.info] Bitcoin network hashrate

[Bitcoin.org] Requirements of Running a Full Node

[Bill Tai] Earth’s Greening and BitCoin Proof of Work. Satoshi is Smiling.